Prison Architect brings unique challenges to the world of management sims

Here’s a game I played with my son when he was little, before he could even walk. I’d sit on the carpet and prop him up between my legs facing a pile of wooden blocks. Then, I’d start building something: a tower, wall, a pyramid, whatever. It didn’t really matter what it was, because his favorite part of the game was to knock the blocks over. Again and again, he’d gleefully smash everything I created, sometimes not even waiting for me to stack more than one block on top of another before giggling adorably and ruining yet another structure.

I totally understood his joy in smashing wooden block constructions, because that’s exactly how I’ve played sim games my entire life. I remember using cheat codes in SimCity 2000 to unleash devastating floods on my burgeoning metropolis. I delighted in making the world’s most unsafe amusement park attractions in Roller Coaster Tycoon. And I never could manage a playthrough in Black & White without teaching my creature some hilariously bad habits.

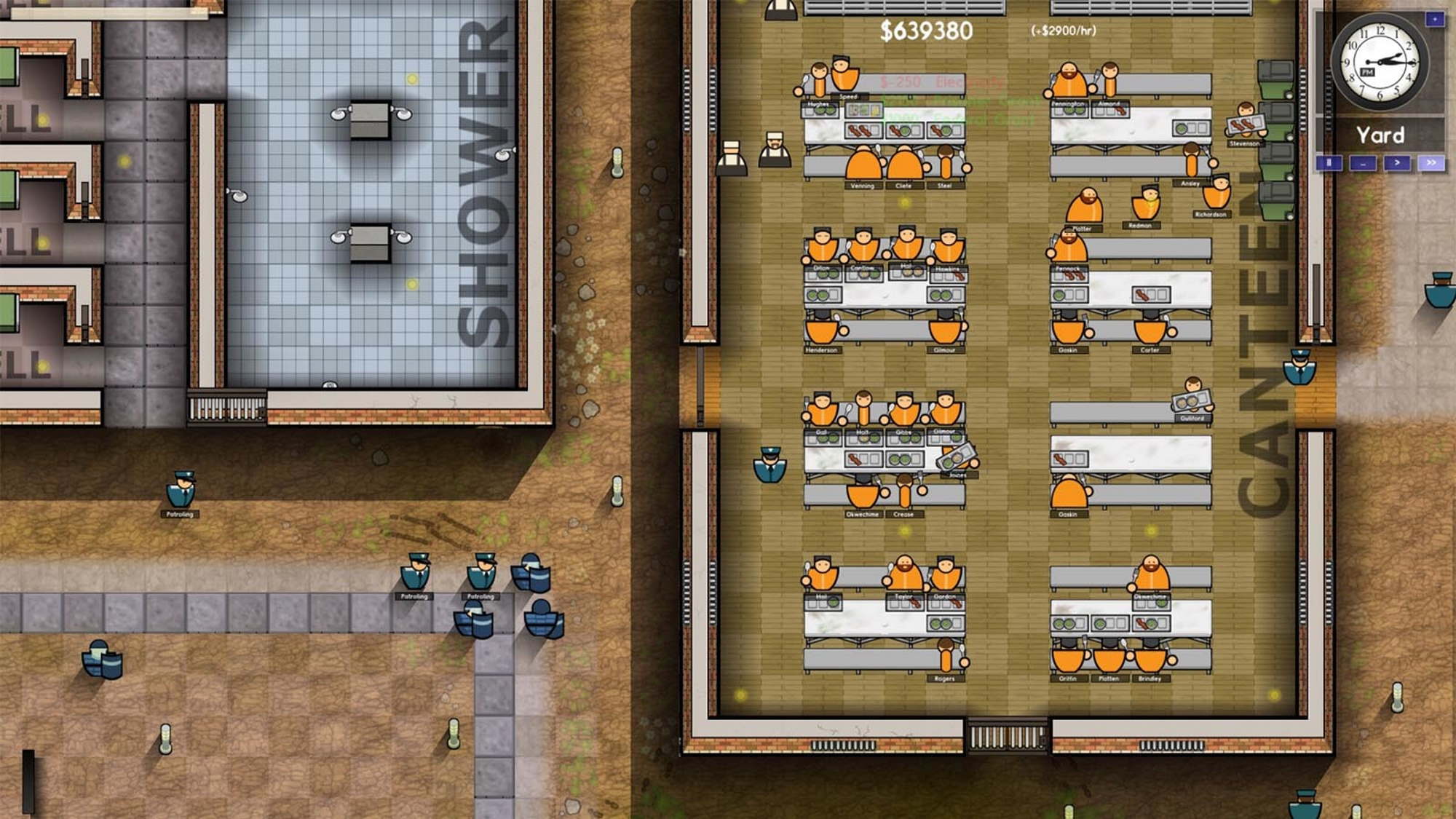

The latest sim in my collection somehow pushed me out of these destructive habits, though. I’m playing Prison Architect, a management sim that tasks me with the construction and daily operations of a prison. On the surface, it provides me yet another playground for making mischief in the lives of virtual people, but the longer I play, the more I get invested in the challenges of running a safe, riot-free facility that effectively rehabilitates criminals into contributing members of society.

Image source: Gamesplanet

Image source: Gamesplanet

Whenever I make a new building, like a cell block or a cafeteria, I first lay out the foundation and the walls. Then, I designate spaces inside for specific functions and provide the basic objects it needs to work. A kitchen, for example, needs a minimum of four refrigerators, four stoves, and a trash can. Then I connect power and water lines as necessary, supply the necessary staff, and customize the building with optional extras like windows and flooring.

In many sims, buildings magically fade into existence as I lay them out. In Prison Architect, workers construct everything sequentially. I get engrossed watching them deliver construction materials from storage before they build out my design square by square and haul in large single pieces like appliances and doors to finish everything off. The depth of the visual simulation adds welcome appeal to the game’s low-res aesthetic.

Image source: Gamesplanet

Image source: Gamesplanet

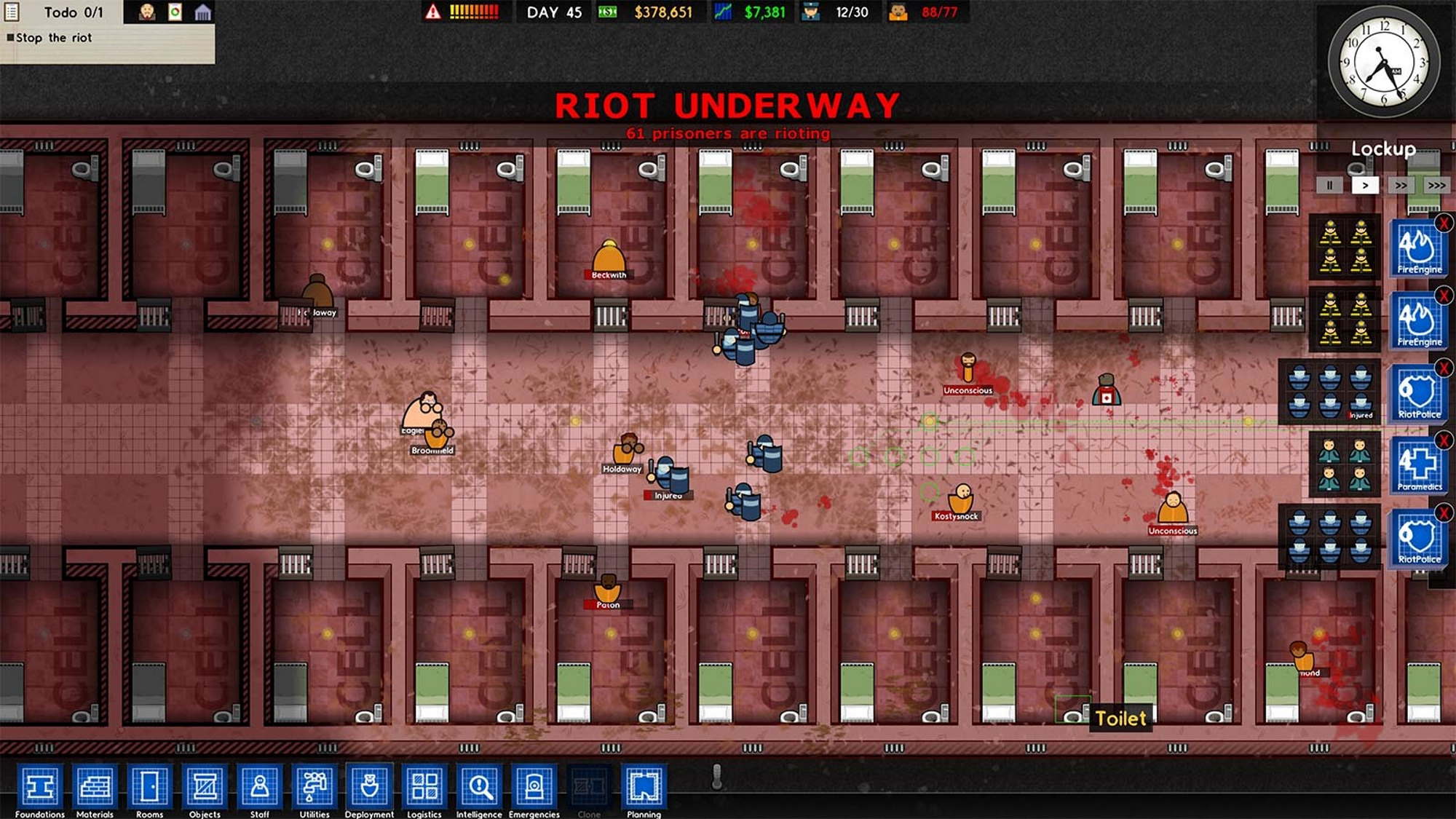

Unfortunately, bad things happen when I get a little too absorbed in my construction projects and neglect the people inside them. That’s a big mistake, because the inmates cause no end of problems. In a typical sim, the population might be a little finicky, but they’re generally happy to be my citizens—at least until I summon a meteor shower. The prisoners, on the other hand, don’t want to be there, and nothing I can do will ever change that. Inmates have a set of needs and desires ranging from food and hygiene to entertainment and drugs, and they’re more or less docile when those needs are met. No matter how much I play nice with them with amenities and luxurious extras, though, they’re always on the lookout for a way to escape, and they rarely pass up a chance to take out their frustrations on each other.

At one point, I had a serious overpopulation problem. I had twice as many inmates as my facility could handle safely. The holding cell that temporarily houses incoming criminals was overflowing because I just didn’t have enough space. Looking back, I should have limited the number of incoming prisoners long before that point to forestall my looming overpopulation problem. I was blinded by all the cash I was making by accepting more prisoners, so I started a grand new construction project: a massive new cell block. I got tunnel vision as I laid out plumbing for the toilets and showers, envisioned wide hallways for my guards to patrol, and carefully placed the entrances.

While I was playing with my wooden blocks, the inmates became increasingly unhappy. Fights were breaking out every day in the holding cell. Prisoners were getting shivved in the canteen. Even my guards were getting beat or up killed as they escorted prisoners to and from meals. By the time my new building was ready for inmates, there was an all-out riot in the prison yard. I had a strong urge to knock everything over and start fresh.

Image source: Gamesplanet

Image source: Gamesplanet

I was far from helpless in that situation, though. Even with the rioters surging across my prison, I had the tools to take control. My first responders against inmate misbehavior are my guards. In peaceful moments, I station them around the prison and send them on circular patrols. When I’m worried that too many prisoners might have contraband like drugs, alcohol, or weapons hidden in their cells, I can send my staff on a search. Guard dogs help to sniff out prisoners attempting to tunnel their way to freedom.

When the prisoners start to fight, my guards will immediately jump into the fray. They’re quite capable, especially if they’ve been bolstered by an on-site armoury, but sometimes the situation will escalate beyond their capabilities. That’s when I call in the big guns. There are a variety of emergency responders I can summon temporarily for emergencies, including riot police, firefighters, and paramedics. If things really get out of control, I can bring in armed guards equipped with shotguns.

I can’t deny that I felt a little angry watching a group of rioters set fire to my latest addition, and got no small amount of satisfaction from putting them in their place. That’s an expensive way to do business, though, and I can’t help but feel responsible for the uprising in the first place. If I’d tried a different layout, if I’d done a better job separating high-risk criminals from the general population, if I’d been just a little more generous with amenities, maybe my janitors wouldn’t be cleaning blood off my new tile floors.

Even more than that, I’d be happier if my prison wasn’t just quiet and orderly, but an institution that effectively rehabilitated criminals. Prison Architect gives me the tools to establish job training programs for inmates, provide treatment for drug and alcohol addiction, and help inmates earn education credentials. Each of these initiatives introduces new complications, though. When I train inmates to work in kitchens or workshops, they try to steal utensils and tools for digging escape tunnels. And the success rate of reform programs is dependent on so many variables that it takes considerable planning, trial, and error to see real progress.

It’ll take some work to get my prison running just the way I want it, but that challenge has really gotten under my skin. I initially liked Prison Architect because it let me indulge that childish glee in building something up only to knock it over, but that’s not why I keep coming back to it. I take pride in walking the game’s tightrope, using heavy-handed force as necessary to maintain order but holding out the promise of a better life to those prisoners willing to invest time in reform programs. All told, Prison Architect is a riveting object lesson in the use of power, and I can’t recommend it enough to fans of the genre.

Auteur

Popular Post

ROG Astral vs Strix vs TUF vs Prime: which ASUS graphics card is right for you?

How to connect the ROG Ally to a TV or monitor for big screen gaming

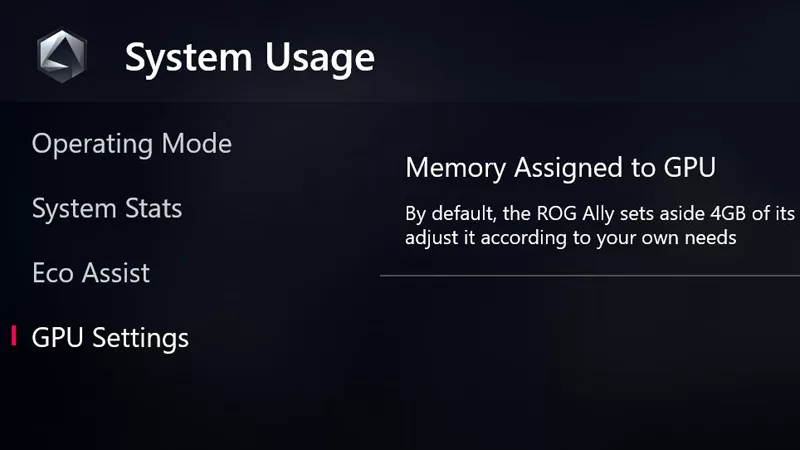

How to increase the ROG Ally's VRAM allocation

How to increase FPS on the ROG Ally with FSR 3 and AFMF 2

ROG Strix SCAR vs Strix G: What's the difference between ROG's esports laptops?

Derniers Articles

The best laptop-friendly PC games you can play without any peripherals

If you want to game on the go without dragging a mouse or controller with you, don’t worry: there’s plenty you can play with just your laptop’s built-in keyboard and trackpad.

Like a Dragon: Pirate Yakuza in Hawaii is absurdist gaming at its finest

Like a Dragon games are playable versions of weird stories a quirky friend might share over coffee. Like a Dragon: Pirate Yakuza in Hawaii is no exception.

Four insane ROG PC gaming battlestations you need to see to believe

Expressing your personality with a tricked-out gaming setup is a core part of the PC gaming experience. No one knows this better than ROG loyalists, who produce some of the wildest battlestations on the planet.

Why Sonic the Hedgehog is the wildest series in gaming

If you’ve been gaming for a while, you probably know SEGA’s Sonic the Hedgehog. But do you know why he commands his own gravitational orbit among a dedicated group of fans?

Savoring Assassin’s Creed Shadows’ living, breathing recreation of 16th century Japan

I’m overjoyed that Assassin’s Creed Shadows puts stealth on a pedestal. But I’m even more psyched that I’ll get to be a sneak king in a game so big and beautiful.

ROG Travel books another killer vacation in second video

Troy Baker and Ned Luke team up to offer a killer vacation plan in a post-apocalyptic paradise.