How Portugal is building an esports scene from scratch

Just 12 minutes beyond Lisbon’s city center, something magical is happening. Kids from eight to 18 line up outside the recently-constructed Biblioteca de Marvila, shading their faces and impatiently peering inside to see if it’s open yet. The good-natured security guard laughs, smiles, and waves.

Today, marks the first-ever Bibliogamers event. It’s the brainchild of library coordinator and director of culture, Paulo José. This might seem like an unlikely role for a former anthropologist-turned-criminologist, but José sees similarities. During his time in the police force, he had to understand the needs of different populations and apply empathy. Now he does the same, but for Marvila. In this former industrial hub, illiteracy is an issue for over 7% of residents—twice as many as Lisbon. Yet José has kids lining up outside a library, practically dancing with excitement. The secret, it turns out, is video games.

Gamers at the Marvila library play a casual game of FIFA ‘17 before the tournament.

Gamers at the Marvila library play a casual game of FIFA ‘17 before the tournament.

Soon after the library opened six months ago, José noticed that some of its younger visitors spent hours playing CS:GO on the library's computers after school, and even more time on weekends. So, he did what any good former investigator would do: “We [met] with them and asked, ‘Why are you [coming] here to play?’ The answer was surprisingly simple: they come to play with friends. At home, they don’t have enough space or PCs.”

Other libraries may have banned gaming completely, but José saw an alternative. After all, he plays World of Warcraft in his own spare time. He decided to embrace it. Games are getting kids in the door, where they're surrounded by books and socializing with friends. José even started questioning why libraries don't offer video games for check-out, aptly noting, “We have DVDs, CDs, books, and board games, but we don’t have video games. Why? It’s a simple question. ”

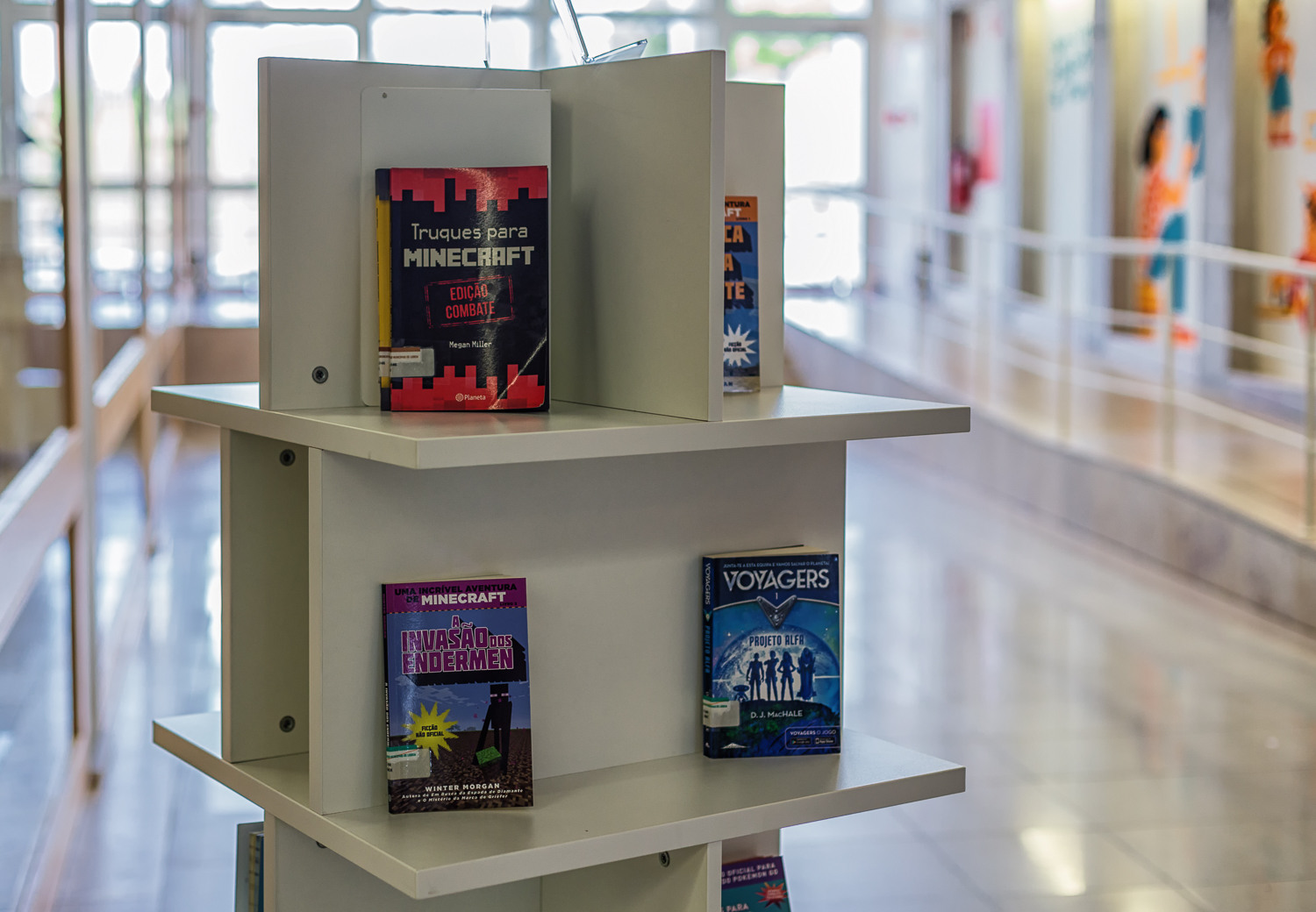

Minecraft and other gaming-themed books on the shelves at Marvila library in Portugal.

Minecraft and other gaming-themed books on the shelves at Marvila library in Portugal.

After some brainstorming, the library staff took it a step further, developing an idea to dedicate a whole month to gaming. Thus, Bibliogamers was born. From a shelf stocked with books on gaming, to LAN parties, seminars, game tournaments, and a HoloLens demo, they went all-out, and they invited ROG to participate.

During the tournament weekend and alongside other Portuguese game developers, we exhibited CS:GO on the ROG Strix GL502VS. The kids absolutely loved it. In between heated FIFA '17 matches, they crowded around the laptop, jockeying for a turn behind the glowing keyboard and cheering each other on during clutch moments.

The ROG Strix GL502VS looked perfectly at home among Marvila library’s modern concrete architecture.

The ROG Strix GL502VS looked perfectly at home among Marvila library’s modern concrete architecture.

Many of the young gamers at Marvila library are simply happy to be playing games with their friends—they aren’t thinking about future jobs. But, for some, gaming will undoubtedly be a prospective career choice. José knows that an interest in playing games today can someday lead to an interest in making them, particularly if it’s encouraged and given room to thrive. For others, the dream is going pro. If only they could marry their love for gaming with a profession—if they could become esports stars—their lives would be complete.

Missing the esports vision

Paulo José, Marvila Library’s coordinator, watches as local gamers play CS:GO on the ROG Strix GL502VS. A World of Warcraft player himself, his stance has been to wholeheartedly embrace gaming at the library.

Paulo José, Marvila Library’s coordinator, watches as local gamers play CS:GO on the ROG Strix GL502VS. A World of Warcraft player himself, his stance has been to wholeheartedly embrace gaming at the library.

“There’s a big problem in Portugal.” João Semedo tells me over coffee. “The problem is the missed vision. There is a cultural gap. People have now started adapting to gaming, but esports is a niche. It doesn’t bring the money, exposure, or sponsors.”

Semedo is the former CEO of the Esports Portugal League (ESPL/NPCL). “Former” because he and his partners recently dissolved it. Frustrated by Portugal’s limited esports investment, he’s now thinking big. From a marketing perspective, he believes esports evangelism and a pro gaming “star system” are both crucial to success.

João wants esports to go mainstream in Portugal, which means getting parents on board, esports on TV, big gaming events on the calendar, and acquiring major sponsors in the country. He points out that even before Portuguese footballer Cristiano Ronaldo was considered the world’s best player, he had a marketing team behind the scenes creating a personal brand. Likewise, until Portuguese pro gaming becomes widely accepted, someone needs to be building up the brand, both for the sport and the individuals.

Maria João Andrade, Portugal’s only gaming and esports psychologist, agrees. She grew up gaming and regularly counsels gamers’ families, so she’s heard it all before: “Families don’t understand the gaming context. It’s hard [for them] to understand what’s a professional gamer or esports.” As a professional pursuing a PhD in esports psychology, she encounters this in academia, too. Until she corrected him, one of her department’s professors thought that “esports” simply meant, “That thing with the Wii.”

Maria João Andrade is both a gamer and Portugal’s first esports psychologist. Just as sports psychologists coach teams to success, she coaches esports teams to victory.

Maria João Andrade is both a gamer and Portugal’s first esports psychologist. Just as sports psychologists coach teams to success, she coaches esports teams to victory.

Industry professionals represent one side of the coin. But gamers also feel the pain, especially when even top tier Portuguese pros rarely make minimum wage.

Gaspar “Hypno” Machado is one such gamer. He’s sponsored to play Unreal Tournament and Quake competitively. When Machado was just 20 years old, he won the biggest UT3 tournament in the world, with a prize pool of $40,000. He’s the world’s number one UT3 player, and Epic Games even invited him to North Carolina to provide input on UT4.

When it comes to esports earnings, Machado is second only to Portugal’s biggest CS:GO player, Fox. Yet, Machado still can’t make a full-time living from gaming. His first big win was over nine years ago and made up almost his entire career earnings. So, for him, “work” isn’t gaming but a full-time job as a VR 3D artist. After a day at the office, he has dinner, practices for three to four hours, then immediately goes to bed. It’s a grueling but necessary schedule. Yet, he considers himself lucky: at least he has a supportive employer.

Gaspar “Hypno” Machado was the world’s number one UT3 player. He’s now a sponsored Quake pro, recently qualifying in the Quake World Championship for a minimum prize pool of $25,000. Even so, earning a full-time living as an esports player simply isn’t feasible.

Gaspar “Hypno” Machado was the world’s number one UT3 player. He’s now a sponsored Quake pro, recently qualifying in the Quake World Championship for a minimum prize pool of $25,000. Even so, earning a full-time living as an esports player simply isn’t feasible.

Pedro “uPRO-Barboza” Barbosa is in a similar situation. A Pro Evolution Soccer player, he’s traveled to London, Manchester, Dubai, Milan, and beyond. In this time, he’s become both a National and European champion. Pro gaming has unlocked new opportunities, but Barbosa still tells me that gaming is a difficult career path in Portugal. He’s been doing it for eight years, and it still isn’t a viable full-time job.

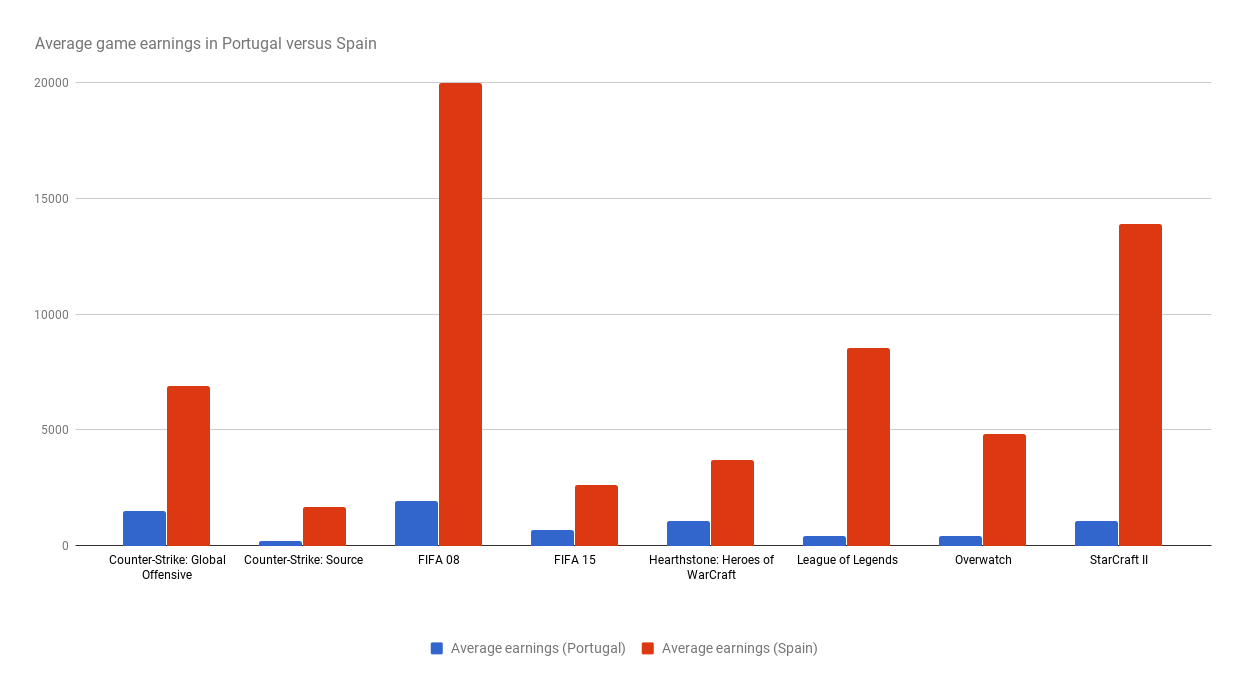

Admittedly, Unreal Tournament 3, Quake, and Pro Evolution Soccer aren’t top-earning titles like CS:GO, DOTA 2, and LoL. They certainly don’t have millions of dollars at stake like The International. But Machado and Barbosa’s problems reflect broader issues faced by many Portuguese pro gamers. Comparing Portugal to its neighbor, Spain, puts things into perspective. The average lifetime earnings for the top 300 CS:GO players in Portugal is just $1,506 USD. In Spain, it's over four times that—$6,885 USD. And this pattern holds true for almost every esports title that’s played in both countries.

Data source: Esports Earnings

Data source: Esports Earnings

Non-Portuguese gamers notice these problems, too. Husband and wife team Marc and Alexandra Berthold moved to Portugal from France and Germany to launch their esports startup. Both are quite familiar with their respective countries’ gaming scenes: Marc is a former Call of Duty 4 world champion, while Alexandra is also an avid gamer.

“The scene here [in Portugal] reminds me of France five years ago,” Marc says. “It’s still underground.” It certainly doesn’t help that most Portuguese teams and leagues lack the resources to send even their most talented players abroad. Portuguese players are boxed in, and the ones who truly want international exposure leave the country altogether. “[They] don’t stick in [their] country to play.”

Case in point: Ricardo “fox” Pacheco, Portugal’s top CS:GO player, left Portuguese team k1ck in 2015. Since then, he’s been working his way up internationally, from Team Kinguin to the British Team Dignitas. To some extent, this happens in esports everywhere. However, it becomes an issue when leaving their home country is pro gamers’ only shot at success. Until more investors and brands start putting money into Portuguese esports, this will continue. Even Pedro Barbosa is waiting for an invitation to someday play in an international league.

Alexandra Berthold echos Marc’s sentiments: Portugal is a stark contrast to Germany’s gaming scene. “In Germany, [...] it can’t be ignored that esports is a huge thing. The impression [in Portugal] is that it’s behind.”

Increasing opportunities, growing optimism

In the same cafe on a different day, I’m struck by how Telmo Silva’s optimism for gaming leagues is the polar opposite of that of João Semedo. The latter sees little point in leagues until esports is more mainstream. In contrast, Silva is actively working on expanding his league internationally.

Silva is the CEO of Grow uP eSports, the oldest and largest pro gaming organization in Portugal. It’s a project he began over 15 years ago, when he was just 16 years old. It's been through many iterations since. First came Underworld Preachers (the “uP” in “Grow uP eSports”), a pro Unreal Tournament ‘99 clan formed with friends. From a clan, to a gaming school, to an esports events company, to a non-profit, it snowballed into something far greater than the sum of its parts. Today, Grow uP supports almost 2,000 players, including running a gaming psychology department in partnership with none other than psychologist Maria João Andrade.

Maria João Andrade shows off Tetris-inspired business cards for Grinding Mind, an organization she founded to support gamers and promote better social understanding of video games.

Maria João Andrade shows off Tetris-inspired business cards for Grinding Mind, an organization she founded to support gamers and promote better social understanding of video games.

Silva acknowledges that Portuguese gamers don’t have the same opportunities as other European pros, particularly players in Sweden, Germany, and France. To counteract this, he’s intentionally using Grow uP as a platform to give his gamers the worldwide exposure and experience they wouldn’t get otherwise. As a former pro, Silva understands the importance of mixing it up. “Players have a different experience [competing] with the best. When you don’t have those opportunities, it’s very difficult.” In 2014, Grow uP sent 30 players to the UK. For many, it was their first time ever setting foot on a plane.

Unlike many other Portuguese esports leagues, Silva has seemingly cracked the code to funding. Grow uP eSports is already one of the oldest gaming associations in Europe. However, they can also operate as a youth nonprofit because over 70% of their members are under 30. Government support lends added credibility during investor discussions. Plus, they don’t kick players and teams out for falling below an arbitrary performance bar. Silva views Grow uP not only as a league, but a family and network. Just as they’ve provided players with international exposure, players have helped with everything from website development to the league’s Macau expansion.

Telmo Silva isn’t the only one bridging this opportunity gap. Entrepreneurs Marc and Alexandra Berthold have a startup called gleetz.gg. A dedicated gaming and esports social network, its goal is helping gamers find teams, sponsors, and opportunities they might overlook. Gleetz already has over 12,000 users, 700 teams, and 300 companies signed up, with more joining daily.

Marc and Alexandra Berthold moved to Portugal to launch their startup. They’ve both noticed that the Portuguese esports scene lags behind much of Europe.

Marc and Alexandra Berthold moved to Portugal to launch their startup. They’ve both noticed that the Portuguese esports scene lags behind much of Europe.

Meanwhile, marketer João Semedo has esports evangelism projects in the works. He’s coaching casters and pro gamers to handle the spotlight, working with psychologist Maria João Andrade on changing parents’ outlook toward gaming, and partnering with one of Europe’s biggest ad agencies for a Portuguese gaming campaign. All of these actions are targeted at prepping the esports scene for major investors, so players can actually make money. “My biggest goal is that [players] are paid for what they do. And after that, my goal is that they’re paid what they’re worth.”

No PC, no problem

Back at the Bibliogamers event, a growing group of gamers gathers around the ROG Strix laptop. Those closest to the screen lean inward with intense focus.

Gamers crowded around the GL502VS all day, playing CS:GO in between FIFA '17 matches.

Gamers crowded around the GL502VS all day, playing CS:GO in between FIFA '17 matches.

After the last match, Alexandre Paixão, a fellow exhibitor, jumps in as an impromptu interpreter, asking the kids what they think of the GL502VS laptop. We quickly discover why they really come here for CS:GO each day: none of them has a PC at home. They’ve never seen anything like the laptop before. They’re totally blown away by its aesthetics and power. It becomes clear that Marvila library isn’t just some place to play games with friends—for many, it’s their only place to play games with friends.

For Paulo José, Bibliogamers is just the beginning. With an excited sparkle in his eyes, he tells me about the library’s plans for the basement of a nearby municipal building. There, they plan to launch a “Gamer Lab” with Maria João Andrade’s organization, Grinding Mind, and the University of Portugal.

Paulo José sketches out rough plans for “Gamer Lab,” a space where he envisions gamers from Marvila and beyond could learn all aspects of the game design process.

Paulo José sketches out rough plans for “Gamer Lab,” a space where he envisions gamers from Marvila and beyond could learn all aspects of the game design process.

By the middle of next year, they hope to start implementing this real-life laboratory where young gamers can learn the game development ropes from start to finish: designing, programming, modeling, testing, and more. Ultimately, José envisions a social movement in Marvila, one where library gamers who grew up without PCs go on to become game designers and developers.

Stubborn. Passionate. Resourceful. These are the terms used to describe the Portuguese gamers pursuing their dreams against the odds. While Portugal’s gaming and esports world is undoubtedly behind the European curve, its community isn’t waiting for the right moment. Quite the opposite, they’re joining together and creating their own opportunities, one library, league, startup, and school at a time.

CS:GO players at Marvila library get into the game.

CS:GO players at Marvila library get into the game.

By Kimberly Koenig

Author

Popular Posts

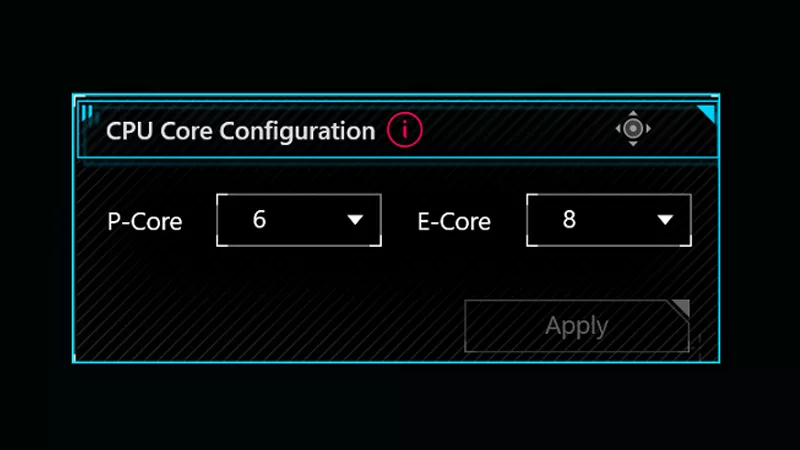

How to adjust your laptop's P-Cores and E-Cores for better performance and battery life

Introducing the ROG Astral GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080: a new frontier of gaming graphics

How to Cleanly Uninstall and Reinstall Armoury Crate

How to configure your PC's RGB lighting with Aura Sync

How to upgrade the SSD and reinstall Windows on your ROG Ally or Ally X

LATEST ARTICLES

Stellar Blade is the stylish, stimulating action romp PC gaming needed in 2025

It’s one thing to look good, it’s another to play well, and it’s a Herculean task to deliver a game that manages both. But Stellar Blade does the job with gusto.

10 must-play ROG Phone 9 games with support for Game Genie and AI features

From FPS to immersive RPGs, check out the best games to play on the AI-enhanced ROG Phone 9 series.

The best laptop-friendly PC games you can play without any peripherals

If you want to game on the go without dragging a mouse or controller with you, don’t worry: there’s plenty you can play with just your laptop’s built-in keyboard and trackpad.

Like a Dragon: Pirate Yakuza in Hawaii is absurdist gaming at its finest

Like a Dragon games are playable versions of weird stories a quirky friend might share over coffee. Like a Dragon: Pirate Yakuza in Hawaii is no exception.

Four insane ROG PC gaming battlestations you need to see to believe

Expressing your personality with a tricked-out gaming setup is a core part of the PC gaming experience. No one knows this better than ROG loyalists, who produce some of the wildest battlestations on the planet.

Why Sonic the Hedgehog is the wildest series in gaming

If you’ve been gaming for a while, you probably know SEGA’s Sonic the Hedgehog. But do you know why he commands his own gravitational orbit among a dedicated group of fans?